Contributed by Cynthia Brown, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Virginia

A 27 year old woman was evaluated for complaints of poor nocturnal sleep quality and excessive daytime somnolence. She reported that her difficulties with sleep began in adolescence when she suffered a closed head injury in an automobile-pedestrian accident. At that time, she experienced a brief loss of consciousness. Throughout high school, she struggled with remaining awake during class.

More recently, her sleepiness has worsened. She reports an Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 21/24. She falls asleep unintentionally whenever she is sedentary and has fallen asleep driving. She also has difficulty with her nocturnal sleep. She typically is in bed from 11 PM until 7 AM. She falls asleep within minutes, but reports repeated nocturnal awakenings of unclear cause. When she awakens, she typically is able to return to sleep quickly. She does not snore. At sleep onset, she has had repeated episodes where she sees someone sitting on the edge of her bed and has infrequent episodes of sleep paralysis. She denies episodes of cataplexy. On physical examination, she is a thin woman with a body mass index of 22.5 kg/m2. Her neurologic examination is normal.

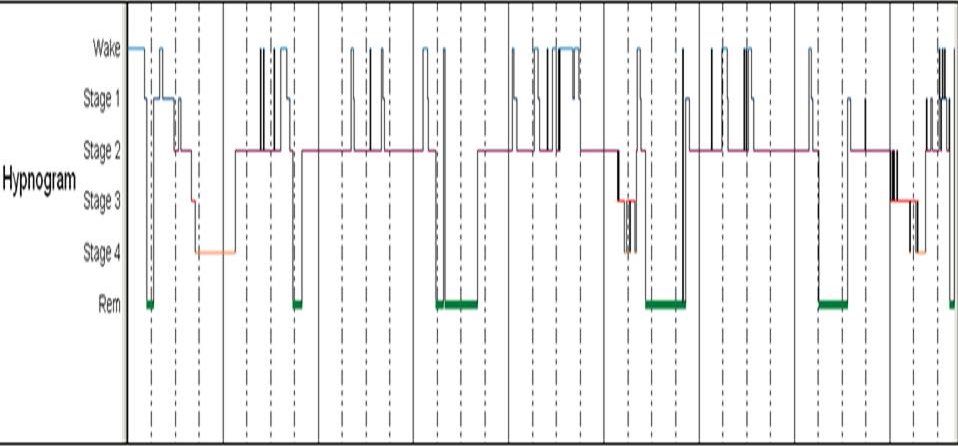

The hypnogram from her nocturnal sleep study is shown below.

Question: What does the hypnogram suggest as the underlying cause of the patient’s hypersomnia? What would you do to confirm the diagnosis?

Answer: The hypnogram shows early onset of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep with multiple spontaneous awakenings suggestive of narcolepsy. A multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) is indicated to confirm the diagnosis.

Discussion: Nocturnal sleep disturbance has been noted to be a key clinical feature of narcolepsy since the seminal publication by Karl Westphal describing narcolepsy with cataplexy in 1880.1 In his case description, Dr. Westphal noted “persistent night-time sleeplessness” was present with his patient reporting only brief episodes of nocturnal sleep.1 Though long-recognized as a symptom of narcolepsy, disturbed nocturnal sleep has not been included as part of the classic tetrad of narcolepsy that includes excessive sleepiness with sleep attacks, hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations, sleep paralysis and cataplexy. However, significant complaints of poor quality nocturnal sleep affect up to 60% of individuals with narcolepsy and are more common than sleep paralysis or hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations.2 Nocturnal sleep complaints in narcolepsy are varied and include frequent awakenings, vivid nightmares, and unrefreshing sleep.

The normal sleep pattern is characterized by entry to sleep through NREM sleep with the first REM cycle occurring 90-110 minutes after sleep onset. In narcolepsy, sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMP) are common and are the characteristic finding on MSLT that defines the diagnosis, particularly in individuals without cataplexy. Prior to the most recent update to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD), the presence of REM sleep within 20 minutes of sleep onset on an overnight polysomnography was part of the diagnostic criteria for narcolepsy. However, this criterion was removed in the second edition of the ICSD as fewer than 50% of individuals with narcolepsy demonstrate this finding on overnight polysomnography.3 In addition to the SOREMP, this patient’s hypnogram has other features that are commonly seen in narcolepsy, including short sleep latency, frequent nocturnal awakenings, and decreased slow wave sleep in the absence of sleep-disordered breathing or periodic limb movements of sleep (not represented on the hypnogram).2 Overall, however, the total sleep time was preserved (473 minutes), which is also characteristic of narcolepsy.2

Over the past fifteen years, the pathophysiology of narcolepsy with cataplexy has been discovered to be related to the loss of neurons that secrete hypocretin (orexin) in the hypothalamus.4 The number of neurons in the hypothalamus that secrete hypocretin are limited to only about 50,000-80,000. However, these neurons project widely throughout the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, thalamus, and brainstem, and serve many functions, including regulation of sleep-wake state. In narcolepsy with cataplexy, significant loss of these neurons has been demonstrated with very low levels of hypocretin-1 present in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).4 In narcolepsy without cataplexy or with atypical cataplexy, median levels of hypocretin-1 are not decreased although 20% will have a CSF hyocretin-1 level that is low.5 It is hypothesized that the pathogenesis of narcolepsy without cataplexy may be the result of partial loss of hypocretin neurons or other abnormalities within the hypocretin pathway.5 Additionally, low CSF hypocretin levels have been demonstrated in other neurological disorders, including following traumatic brain injury and Parkinson disease.5

Clinically, determination of CSF hypocretin-1 levels is not indicated in individuals with typical cataplexy symptoms. Most experts recommend testing CSF hypocretin-1levels only in individuals with atypical cataplexy symptoms or in whom the interpretation of the MSLT is confounded by nocturnal sleep disorders or poor quality testing.5

In this individual, a closed head injury preceded the onset of excessive daytime sleepiness. As the patient presented more than 10 years after the head injury, it is difficult to truly assess the temporal relationship of the head injury with development of narcolepsy symptoms. However, post-traumatic narcolepsy (with and without cataplexy) has been reported in the medical literature for more than 60 years.6 Acutely following a moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury, CSF hypocretin-1 levels have shown to be low in as many as 95% of individuals. However, over time, CSF hypocretin-1 levels return to normal values in most individuals.5 Pathologically, loss of hypocretin-secreting neurons has been demonstrated in autopsy specimens following severe traumatic brain injury.5 However, as closed head injury is rather common in the population, developing a definitive epidemiologic link between head injury and incident narcolepsy is difficult.7

No specific treatment for disturbed nocturnal sleep in narcolepsy is currently recommended. However, a variety of agents have been used including sedative-hypnotics and antidepressants with limited evidence to support their usage.2 Recently, use of sodium oxybate has been found to be effective for the treatment of cataplexy and excessive daytime somnolence in individuals with narcolepsy.8 Furthermore, clinical trials have shown sodium oxybate to have a favorable effect on nocturnal sleep quality with an increase in slow wave sleep and decreased nocturnal awakenings.8,9

The day following her overnight polysomnogram, the patient underwent a MSLT. The average sleep latency during the MSLT was 1.4 minutes (median 1.6 minutes), and SOREMP were present in all naps. Upon further questioning, the patient disclosed cataplexy-like episodes where she would feel weakness in her arms that lead to fear that she would drop her young child. These episodes were brought about by surprise and laughter.