What White Lungs You Have

Julia X. Lee1, MD, Daniel T. Atwood, MD1, Kenan Haver, MD1

1Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; Division of Pulmonary Medicine, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Case

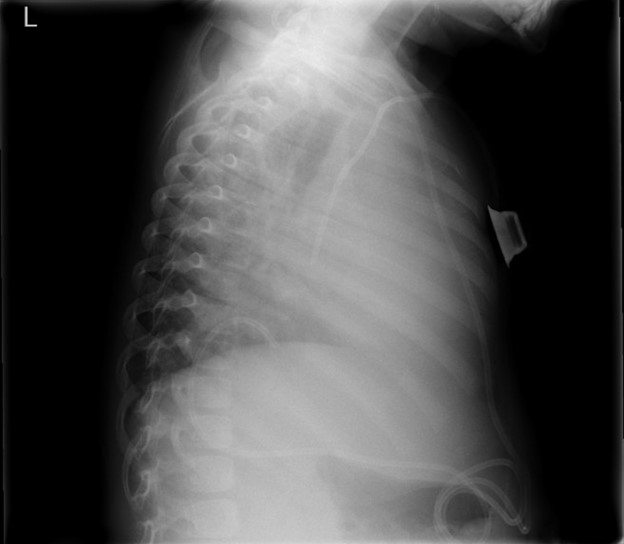

A 4-year-old-girl with anaplastic ependymoma complicated by central sleep apnea and hydrocephalus status post ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement two years prior presented to pulmonary clinic with worsening hypoxemia. Her sleep apnea is managed with nasal cannula due to intolerance of BiPAP. Over the past few weeks, her nighttime oxygen requirement slowly increased from 1L/min to 3L/min. On an unprompted random daytime check, her oxygen saturation was 80%, which improved with 1L/min of supplemental oxygen. She was slightly fussy but otherwise her neurologic baseline with no new fever, cough, difficulty breathing, cyanosis, or fatigue. Her vitals in clinic were as follows: temperature 36.4 °C, heart rate 75 bpm, respiratory rate 20 bpm, SpO2 98% on 1L/min. Her left lung sounds were markedly diminished on auscultation. A chest radiograph was obtained.

Question

What is the most likely cause of this patient’s presentation?

- Infection

- Iatrogenic

- Cardiac

- Malignancy

B. Iatrogenic

Discussion

The chest radiograph demonstrates complete opacification of the left hemithorax with rightward mediastinal shift, concerning for a large pleural effusion and for the development of tension physiology. The ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) can be traced down the anterior chest before tortuously looping up above the right hemidiaphragm to terminate at the level of T10. This suggests that the VPS tip migrated into the left hemithorax, resulting in pleural effusion seen as opacification that obscures the left hemidiaphragm (answer B). Follow up CT chest confirmed the catheter tip ascending into the left pleural space with associated large pleural effusion and complete atelectasis of the left lung.

Clinical presentations of pleural effusion are dependent on the underlying cause, baseline cardiac and pulmonary status of the patient, the rate of fluid accumulation in the pleural space, the rate of fluid drainage, and the lymphatic resorptive capacity. Poor tolerance can be seen in cases where the rate of accumulation is faster than the rates of drainage and resorption. This patient’s history suggests an indolent process in which the shunt migrated at some point prior (unsure weeks or months), causing the patient to become progressively more symptomatic as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) accumulated in her pleural space.

Pleural effusions are the most common presentation of thoracic VPS displacement in children. Migration can be supradiaphragmatic (in which the shunt travels through the chest wall) or transdiaphragmatic (in which the shunt travels through the diaphragm). This can occur due to imbalances in the positive abdominal pressure and negative intrathoracic pressure favoring displacement into the thorax. Inflammation from the shunt tip at the diaphragm can cause local erosion thus creating a path for the catheter. The CSF continues to drain, eventually overtaking the absorptive capacity of the pleura, resulting in pleural effusions. Of note, pleural effusions can also occur in patients with VPS who do not have shunt migration. This may be due to congenital diaphragmatic defects (foramen of Bochdalek or foramen of Morgagni), which are unfortunately very difficult to visualize on imaging. In addition, there may be impairment in the peritoneum’s absorptive capacity resulting in accumulation of CSF in the peritoneal cavity followed by diffusion to the pleural space.1

Other less likely causes of pleural effusion in this patient are of infectious, cardiac, or malignant etiologies (answers A, C, and D). Regarding infectious causes, bacterial pneumonia is the most common cause of pleural effusion in both children and adults, with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae being the most common pathogens. These patients tend to present more quickly with acute respiratory symptoms and fever, rather than with slow increase in oxygen requirement over weeks to months. Pleural effusions can also result from pathologies that increase left atrial or pulmonary capillary wedge pressure leading to left heart disease.2 Patients present with symptoms associated with heart failure in addition to pleural effusion. Pleural effusions from malignancy result from tumor compression, obstruction, or invasion of pleural surfaces or pulmonary lymphatics. In addition to the general respiratory symptoms associated with pleural effusions, patients may have fevers, weight loss, night sweats, lymphadenopathy, and fatigue. 3 Anaplastic ependymomas rarely metastasize outside the central nervous system, albeit there are reports of cases in the thorax, liver and lymph nodes.4

This patient was admitted to the ICU. A left chest tube was placed with one liter of clear output. Pleural fluid grew Staphylococcus epidermidis, and she was started on broad spectrum antibiotics. She underwent VPS externalization and EVD placement. The diaphragmatic hole created by the transdiaphragmatic migration of the shunt was repaired. After two weeks, her shunt was internalized into her peritoneum and she was discharged home. At pulmonary follow up a month after her hospitalization, she was doing well and back to her baseline oxygen requirement.

References

-

Porcaro, F., Procaccini, E., Paglietti, M.G. et al. Pleural effusion from intrathoracic migration of a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt catheter: pediatric case report and review of the literature. Ital J Pediatr 44, 42 (2018).

-

Efrati O, Barak A. Pleural Effusions in the Pediatric Population. Pediatr Rev. 2002;23(12):417-426. doi:10.1542/pir.23-12-417

-

Cashen K, Petersen TL. Pleural Effusions and Pneumothoraces. Pediatrics in Review. 2017;38(4):170-181. doi:10.1542/pir.2016-0088

-

Kumar P, Rastogi N, Jain M, et al. Extraneural metastases in anaplastic ependymoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2007;3(2):102–104. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.34689.