Postoperative Bleeding… in the Airway?

Richard Ramonell, MD, Charles Terry, MD, Laurence W. Busse, MD, and Alejandro Sardi-Freitez, MD

Emory University School of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine

Case

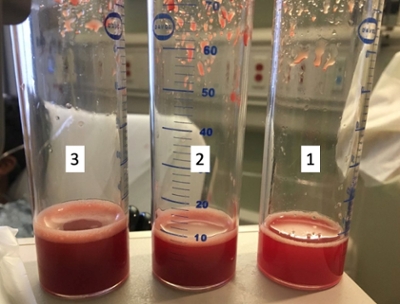

A 36-year-old male is admitted to the intensive care unit for new-onset, non-massive hemoptysis and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure one day after surgical repair of his anorectal fistula at an outside hospital. Intraoperatively, there was no report of difficult intubation, problems with sedation, or dyssynchrony with the ventilator. He was extubated to room air and discharged without supplemental oxygen but presented to our emergency department when he became acutely short of breath and developed hemoptysis. His past medical history includes mild intermittent asthma and an anal abscess complicated by an anorectal fistula. Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of the right lower lobe. Sequential returns during BAL are shown below and are labelled 1, 2, and 3 based on the order they were obtained. A representative Chest CT image and bronchoscopic images are shown below.

Images

Question

Based on these images and the character of the BAL fluid, what is the most likely cause of the patient’s hemoptysis?

- ARDS

- Tuberculosis

- Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Goodpasture Syndrome

C. Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage

Discussion

The chest CT image above show diffuse ground glass opacities, predominantly in the bilateral lower lobes. The bronchoscopic images show dark red blood in the proximal airways and the three traps containing fluid from BAL. After BAL with three sequential 60 mL aliquots of normal saline, the return became progressively bloodier which is diagnostic of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH). The patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit and was placed on high-flow nasal cannula while autoimmune, infectious, inflammatory, pulmonary vascular, and malignant causes of DAH were pursued. Concurrently, the outside hospital was contacted, and it was revealed that patient had received general anesthesia with sevoflurane for his recent surgical procedure. All BAL cultures were negative, as were blood cultures and a respiratory viral panel. Autoimmune serologies including ANA, anti-PR3 antibody, anti-MPO antibody, and anti-GBM antibody were negative, studies of coagulation were normal, and the rest of the workup was negative. The patient rapidly improved and was discharged home on room air without any immunosuppressive agents or antimicrobials. At discharge, the final diagnosis was sevoflurane-induced DAH.

DAH is an uncommon cause of hemoptysis and can have severe consequences if not recognized clinically. DAH is defined as diffuse intra-alveolar accumulation of erythrocytes and can arise from a variety of pathologic conditions (1). Patients with DAH commonly present with hemoptysis and diffuse opacities on chest radiography. Many patients, depending on the chronicity of the alveolar hemorrhage and underlying etiology, can also present with microcytic or normocytic anemia, as did the patient in this case. Pulmonary function testing can be normal or may show restriction to ventilation in cases of chronic DAH. Acute DAH can cause an increase in the diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO) secondary to binding of carbon monoxide to hemoglobin that has extravasated into the alveolar space (1).

DAH can be broadly classified by its chronicity and by its underlying cause. In general, causes of DAH can be categorized into disorders of coagulation, capillaritis, diffuse alveolar damage, bland pulmonary hemorrhage, and idiopathic (2). Depending on the medication, all four aforementioned etiologies are possible pathogenic mechanisms for DAH. For example, propylthiouracil and phenytoin cause a pulmonary capillaritis, amiodarone and nitrofurantoin cause bland pulmonary hemorrhage, and crack cocaine causes diffuse alveolar damage (2). Sevoflurane is an inhaled anesthetic gas frequently used in general anesthesia that has been associated with DAH (3, 4). Although no definitive mechanism for sevoflurane-induced DAH has been elucidated, theories include direct endothelial damage or pulmonary toxicity from the main metabolite of sevoflurane, fluoromethyl- 2,2-difluoro-1-(trifluoromethyl) vinyl ether (4). Although no large case series of sevoflurane-induced DAH are available, patients are expected to improve with withdrawal of the offending agent, as the patient did in this case.

References

-

Murray, J. F. and Nadel, J. A. (2010). Textbook of Respiratory Medicine (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

-

Lara AR, Schwarz MI. Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage. Chest. 2010; 137(5): 1164–71.

-

Kim CA, Liu R, Hsia DW. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage induced by sevoflurane. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014; 11(5): 853-5.

-

Austin A, Modi A, Judson MA, and Chopra A. Sevoflurane Induced Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage in a Young Patient. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports 2017; 20: 14-15.