Point of Care Changing the Place of Care

Adil Alexander Yunis, MD1, Jeffrey A Fowler, DO1, Phillip Edward Lamberty, MD2.

1Heart and Vascular Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA,

2Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA

Case:

A 59-year-old male presented to the emergency room with four days of progressive dyspnea on exertion after a long drive. On the day of admission, he experienced sudden worsening dyspnea at rest. His past medical history was significant for hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and tobacco use.

Exam: HR 110, BP 106/61, RR 24, SpO2 100% on 6L NC. Lungs: Clear to auscultation

Labs: WBC 14.9, Hg 11.7, PLT 221, lactate 1.1, Troponin I 0.06, BNP 856.

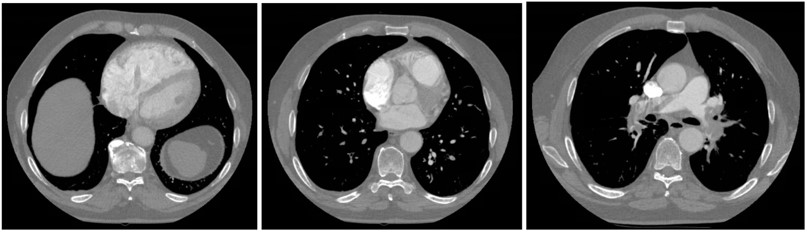

Imaging: CTPA

Question:

What is the diagnosis:

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pulmonary embolism with clot in transit

- Pulmonary embolism with clot in transit and impending paradoxical embolism

- Tricuspid Valve endocarditis

C. Pulmonary embolism with clot in transit and impending paradoxical embolism

Discussion:

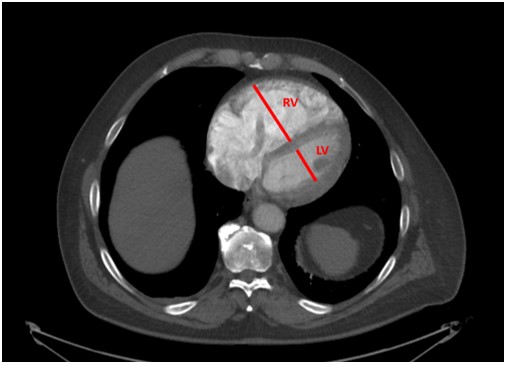

CTPA filling defects in the right and left main pulmonary arteries consistent with acute pulmonary embolism. The right ventricle (RV) was severely dilated with an RV/LV diameter ratio of > 2, a strong predictor of early death in patients with acute PE (1)

Imaging and laboratory evidence of RV dysfunction with a simplified PESI score of 3 classified this as a submassive / intermediate-high risk PE and the patient was referred for catheter-based intervention.

Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) was performed prior to the start of the procedure.

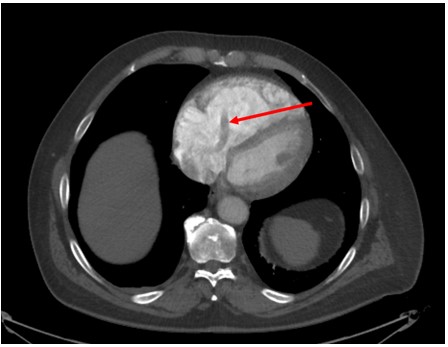

POCUS revealed an 8.7 cm x 1.9 cm mobile echodensity in the RA, prolapsing into the RV, crossing a patent foramen ovale (PFO) into the LA, consistent with clot in transit (CIT). POCUS also showed RV hypokinesis with preserved apical function (McConnell’s sign).

The patient was sent for emergent surgical thrombectomy and PFO closure given the risk for paradoxical embolism. The CIT was successfully removed intact (pictured below) as were multiple pulmonary arterial clots, and he was discharged home 8 days later.

While CTPA remains the method of choice for diagnosing PE, POCUS provides crucial data for risk stratifying sub-massive PE such as RV strain and CIT. In retrospect, the patient’s CTPA exhibited evidence of the CIT with a tubular filling defect in the right heart. In retrospect, a LA filling defect adjacent to the RA was detected on CT consistent with clot traversing a PFO.

Labelled CT scan and cardiac ultrasound

The prevalence of CIT in the setting of PE is approximately 7-18%, but with increased use of POCUS this number is likely to rise (2,3). The diagnosis of CIT has prognostic significance as the overall mortality rate for PE with CIT has been reported as exceeding 40% (4). Rapid intervention is warranted, due to the risk for embolization to the pulmonary arteries and circulatory collapse. Traditional treatment with surgical embolectomy and systemic thrombolytics demonstrates similar outcomes in observational studies (5). Based on case reviews, surgery may be the preferred treatment in the rare event of a CIT traversing a PFO, allowing for both embolectomy and PFO closure (6)

Routine echocardiography in all PE cases is controversial, but its use remains advisable for higher risk patients with PE by facilitating further risk stratification through the assessment of RV function and detection of CIT (7). The use of POCUS to diagnose our patient’s CIT crossing a PFO was critical in selecting surgical embolectomy rather than catheter-based techniques.

References

-

Schoepf UJ, Kucher N, Kipfmueller F, et al. Right Ventricular Enlargement on Chest Computed Tomography. Circulation. 2004;110 (20): 3276-3280

-

Chapoutot L, Nazeyrollas P, Metz D, et al. Floating right heart thrombi and pulmonary embolism: diagnosis, outcome and therapeutic management. Cardiology.1996; 87:169–174

-

Casazza F, Bongarzoni A, Centonze F, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of right-sided cardiac mobile thrombi in acute massive pulmonary embolism. American Journal of Cardiology.1997; 79:1433

-

European Working Group on Echocardiography. The European Cooperative Study on the clinical significance of right heart thrombi. European Heart Journal. 1989; 10:1046–1059

-

Chartier L, Béra J, Delomez M, et al. Circulation. 1999; 99(21):2779-83.

-

Baydoun H, Barakat I, Hatem E, et al. Thrombus in transit through patent foramen ovale. Case Reports in Cardiology. 2013; 2013:395879

-

Rivera‐Lebron BN, McDaniel M, Arhar K, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and follow up of acute pulmonary embolism: consensus practice from the PERT consortium. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 2019; 25:1–16.