Pediatric anemia: A bloody mess

Kevin Kaplan, M.D 1,2,3., Amee Revana, D.O. 1,2,3, David R. Spielberg M.D. 1,2

1 Department of Pediatrics Baylor College of Medicine Houston Texas USA

2 Section of Pediatric Pulmonology Medicine Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital

3 Sleep Medicine Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital

Case

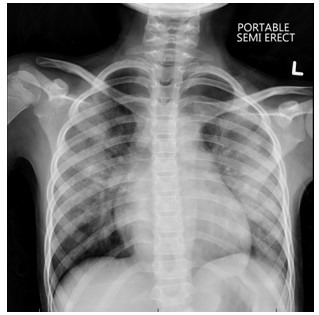

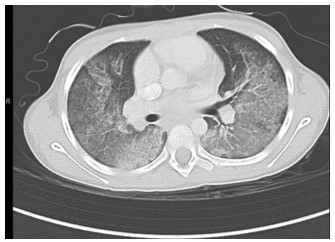

A 9-year-old female with a past medical history of iron deficiency anemia and short stature presents to the emergency department with fever (Tmax 102F). Decreased appetite, fatigue, and leg pain have also been present for 2 weeks. In the ED, vital signs are normal except for tachycardia (HR 130s, SpO2 100% in room air). Review of systems is negative for weight loss, headache, vision change, rhinorrhea, cough, shortness of breath, diarrhea, emesis, or travel. On exam she has tachycardia with no murmur, gallop, or rubs. Lung exam is clear bilaterally. Abdominal exam is positive only for flank pain. Her complexion is pale with a capillary refill less than 2 seconds. Initial lab results show severe anemia (HGB 1.7/HCT 7.5) with normal LDH (698) and uric acid levels (3.4). Peripheral smear is consistent with a history of iron deficiency anemia. A chest film shows diffuse bilateral infiltrates (Figure 1). A chest CT with contrast is performed (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Chest radiograph

Figure 2. Chest CT with contrast

Question

What are the imaging findings suggestive of?

- Community acquired pneumonia

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Viral pneumonia

- Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage

- Miliary tuberculosis

D. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage

Discussion

Imaging results suggest a diagnosis of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH). DAH was confirmed with bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage showing frank blood in the airways and in the alveolar wash.

Pulmonary hemorrhage is due to bleeding from either the arterial or bronchial pulmonary circulation. Bleeding from the pulmonary arterial circulation, seen in DAH, is typically slow and insidious as the hemorrhage is from a high-volume low-pressure system. In contrast, bleeding from the bronchial circulation is typically rapid and of larger volume as it originates from a low-volume high-pressure system. Hemorrhage can be the result of inflammation or injury to the arterioles, venules, or alveolar septal capillaries. The etiologies of pulmonary hemorrhage are broad including infectious processes, aspirated foreign objects, bronchiectasis, vasculitis, congenital lung lesions, congenital heart disease, pulmonary vascular disorders, pulmonary masses, trauma, toxic inhalations, and coagulopathy or thrombosis issues. Some cases, particularly of DAH, remain idiopathic.

Symptoms of DAH are classically cough, hemoptysis, fever, and dyspnea. Importantly, hemoptysis can be absent in 33% of patients, such as in our case presentation. The history should focus on timing and volume of hemoptysis, fevers, choking events, drug exposures, and extra-pulmonary manifestations such as hematuria or signs of gastrointestinal bleeding. Physical examination should evaluate for bruising, crepitus, telangiectasias, hemangiomas, digital clubbing, or focal findings on pulmonary auscultation. Evaluation of the upper airway to identify sources of bleeding from the nasopharynx and oropharynx is essential. Chest radiographs can be non-specific with patchy or diffuse opacities, necessitating a chest CT with angiography for further diagnostic assessment. Laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count, coagulation studies, and an evaluation for infectious, inflammatory, and rheumatologic processes. Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage is indicated to inspect the airways for a source of bleeding, to collect cultures, assess for alveolar bleeding, and look for hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages appear 72 hours after the onset of bleeding and can persist for weeks. Lung biopsy should be obtained in cases of persistent DAH if no cause of the hemorrhage is identified.

Initial treatment for DAH includes supportive care, which can include supplemental oxygen support, mechanical ventilation, and in extreme cases, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. High dose corticosteroids are often utilized while awaiting a final diagnosis. Treatment depends on the underlying etiology, but corticosteroids, immunosuppression, and plasmapheresis are often utilized.

Our patient was admitted for further work-up; after an extensive evaluation, the cause of her DAH remains unclear and she is diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis.

Incorrect responses

-

Community acquired pneumonia (CAP) is an infection of the pulmonary parenchyma. CAP typically presents with fever, dyspnea, cough, and sputum production. Chest radiographs will show a pulmonary infiltrate, but not the diffuse pattern present in this case.

-

Iron deficiency anemia is the most common nutritional deficiency in children with a higher prevalence rate among children living in poverty. Prolonged iron deficiency can be the cause of marked anemia but should not produce changes on chest radiographs or CT.

-

Viral pneumonia can present with fever, dyspnea, cough, and sputum production just as CAP. Chest radiographs often show bilateral opacities. Viral infections can affect the bone marrow and cause anemia, but the severe anemia and diffuse infiltrates in this vignette would make viral pneumonia unlikely.

-

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is a common presentation of TB in children. Symptoms can include cough, fever, weight loss or failure to thrive. Radiographic features of TB depend on the presentation; primary pulmonary, post-primary pulmonary, or miliary pulmonary TB. Miliary TB is caused by hematogenous spread of the infection. Chest radiographs show interstitial septal thickening and diffuse nodules, 1-3 mm in diameter, which are uniform in size and distribution. The opacities seen in our case show a diffuse alveolar process in contrast to a uniform nodular presentation expected in miliary TB.

References

-

Krause, M.L., Cartin-Ceba R., Specks, U., and Peikert T. Update on Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage and Pulmonary Vasculitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2012; 32(4): 587-600.

-

Lara, A.R and Schwarz MI. Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage. Chest 2010; 137: 1164-1171

-

Susarla S.C. and Fan L.L. Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage Syndromes in Children. Current Opinion in Pedaitrics. 2007. 19(3):314-320.

-

Park, J.A., Treatment of Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage: Controlling Inflammation and Obtaining Rapid and Effective Hemostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021. 22(2):793