Looked for a Pulmonary Embolism, Found Something Else

Authors: Michael Sunnaa MD1, Vanessa Fu MD1, Shveta Thakkar MD1, Frank Tenuto MD1

Case

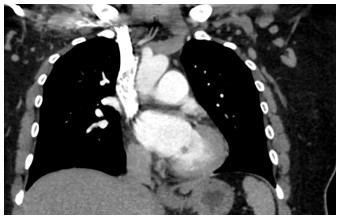

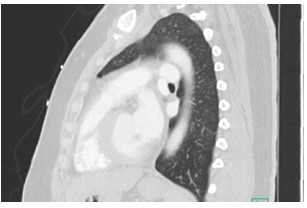

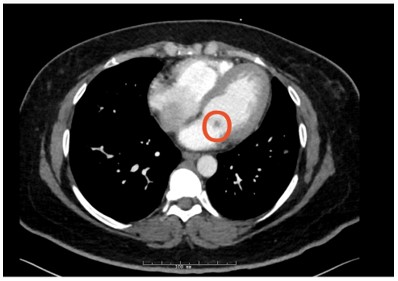

A 41 year old female with a past medical history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), triple-positive antiphospholipid syndrome (APLS), and prior right lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) presented to the emergency department with right lower extremity swelling, cough, and lightheadedness. Of note, the patient reports compliance with her rivaroxaban, and she was not on any immunosuppressive therapy for her lupus after being lost for follow-up years prior. Vitals on arrival were notable for tachycardia, and initial labs showed pancytopenia. A Computed Tomography Pulmonary Arteriogram (CTPA) was obtained (figures 1-3).

Figure 1: Coronal CTPA of the chest

Figure 2: Sagittal CT of Chest

Figure 3: Axial CTPA of Chest

Question

What is the finding?

- Left Ventricular Aneurysm

- Aortic Root Abscess

- Mitral valve mass

- Ventricular septal defect

- Aortic Dissection

Answer C - Mitral valve mass

Figure 4: Circled mitral valve mass (hypodensity)

Discussion

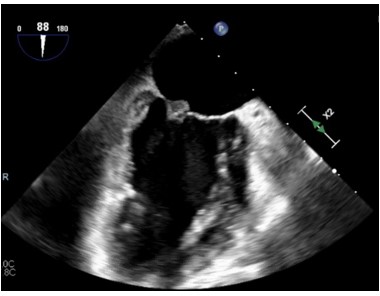

The CT findings were suggestive of a mitral valve mass (answer C), and further work up with an echocardiogram confirmed a 10 mm x 9.1 mm mass on the atrial surface of the posterior mitral valve leaflet (figure 5) with unremarkable findings on the other cardiac valves. Given her rheumatologic history this mass was suspicious for Libman Sacks Endocarditis (LSE). Another possibility for this patient’s mitral valve mass outside of LSE was infective endocarditis (IE). The patient’s hospital course was complicated by intermittent fevers and hypotension, and she was empirically treated for infective endocarditis. Blood cultures prior to antibiotic administration revealed no growth, and patient denied history of intravenous drug use. Thus, given her rheumatologic history, there remained high concern for LSE, for which she was started on hydroxychloroquine and prednisone. She was transitioned from rivaroxaban to low molecular weight heparin given her history of APLS and DVT. The patient was also discharged on IV antibiotics since her Duke's Criteria were consistent with ‘possible for IE’ given her fever, vascular phenomena (splenic infarcts on CT) and evidence of endocardial involvement.

Libman-Sacks endocarditis is a form of nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) which involves the presence of sterile vegetations on the heart valves. The initial process of LSE development appears to be endothelial injury in the setting of hypercoagulable state1, which in our case is both SLE and APLS. Vegetations in LSE are frequently left-sided with two-thirds of cases involving the mitral valve, however, up to a quarter involve the aortic, and less commonly, both valves2. SLE is frequently accompanied by the presence of APLS, which is associated with a higher prevalence of valvular abnormalities in SLE patients3 which was also observed in our patient. Given our patient has a history of triple positive APLS, this put her at higher risk of NTBE than single or double positive APLS4.

Overall, this case exhibits the left-sided and more specifically the mitral preference of LSE and the difficulties in diagnosing LSE vs IE, while also showcasing the importance of using the modified Duke’s Criteria in a patient with whom may be diagnosed as only LSE. LSE and IE share similarities in that they both lead to valvular damage and vegetations1, and that both conditions can lead fevers, malaise, and elevated inflammatory markers5. Ultimately, to differentiate between IE and LSE, a thorough evaluation is needed. Reviewing the patient's medical history and clinical judgement can help guide further. Other clinical features such as of positive blood cultures, or which valves are affected can provide further clues to the underlying etiology. But as evidenced in our case, IE was still “possible” by Duke’s criteria, and thus needed to be accounted for and treated for simultaneously to LSE.

Figure 5: Echocardiogram demonstrating mitral valve mass

References

-

Ibrahim, A. M., & Siddique, M. S. (2022). Libman Sacks Endocarditis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

-

Behbahani, S., & Shahram, F. (2020). Electrocardiogram and heart rate variability assessment in patients with common autoimmune diseases: a methodological review. Turk Kardiyoloji Dernegi arsivi : Turk Kardiyoloji Derneginin yayin organidir, 48(3), 312–327. https://doi.org/10.5543/tkda.2019.21112

-

Hojnik, M., George, J., Ziporen, L., & Shoenfeld, Y. (1996). Heart valve involvement (Libman-Sacks endocarditis) in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Circulation, 93(8), 1579-1587. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.93.8.1579

-

Lenz, C. J., Mankad, R., Klarich, K., Kurmann, R., & McBane, R. D. (2020). Antiphospholipid syndrome and the relationship between laboratory assay positivity and prevalence of non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH, 18(6), 1408–1414. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14798

-

Shoenfeld, Y., & Meroni, P. L. (2006). Heart valve involvement (Libman-Sacks endocarditis) in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Circulation, 113(6), e183–e186. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.592909