Clogged up Lungs

Puebla Neira, D. MD1. Angelova, E. MD2, PhD, Nishi, S. MD1.

1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. 2Department of Pathology.

University of Texas Medical Branch

301 University Boulevard

Galveston, TX 77555

Case

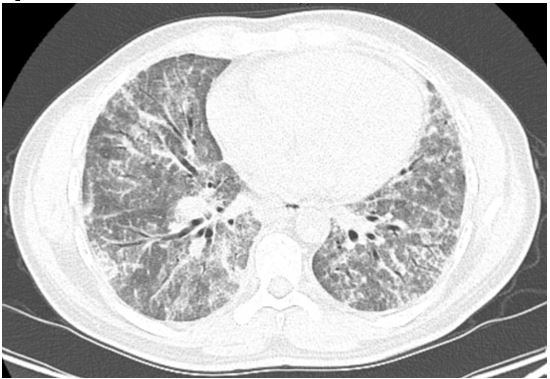

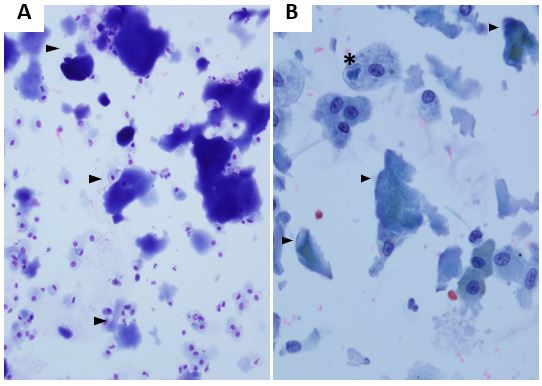

A 41-year-old male construction worker without significant past medical history presented to the ER complaining of non-productive cough, shortness of breath, profound fatigue, unintentional weight loss (15 lbs in one month) and fever worsening over several weeks. He was admitted to the hospital and diagnosed with multilobar pneumonia based on initial chest radiography (CXR). He was treated with antibiotics and 3 liters of supplemental oxygen. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed diffuse ground glass infiltrates predominantly in the lung bases without evidence of pulmonary embolism (Figure 1). A bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was done for cell counts, cultures and cytopathology (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Question

What is the diagnosis?

- Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

- Idiopathic non-specific interstitial pneumonia

Answer: D. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

Discussion

A high level of suspicion based on the combination of clinical, laboratory and radiographic data is necessary to diagnose this disease. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis is characterized by accumulation of Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive lipoproteinaceous material in the distal airspaces1. The lipoproteinaceous material (mostly surfactant phospholipid and apoproteins) is the result of a variety of disorders that affect the production and clearance of surfactant. The etiologies can be autoimmune, hereditary, congenital or secondary to high level dust exposures, hematologic malignancies or after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation1 (Table 1).

The clinical presentation is nonspecific. Most patients have progressive shortness of breath, dry cough that worsens insidiously. Other symptoms include chest pain, fatigue, joint pain, chills, weight loss, and hemoptysis. Fever is unusual and should raise the suspicion of infection. Physical exam findings are not specific and include rales, digital clubbing and cyanosis (severe cases) 1.

A CXR finding of “bat wing” infiltrates (prominent perihilar region infiltrates) can be found in this disease although it is not pathognomonic. HRCT of the chest demonstrates patchy or diffuse infiltrates (ground glass or consolidation). Often “crazy-paving” pattern (Figure 4) on CT imaging is found and represents interlobular septal thickening. Pulmonary function testing can show restrictive changes with decreased diffusion capacity. Intrapulmonary shunt physiology results in hypoxemia which can be profound1.

Additionally, GM-CSF auto-antibodies can be elevated, especially in cases of autoimmune disease. Tissue sampling, either via bronchoscopic BAL or surgical biopsy is necessary to confirm the presence of lipoproteinaceous material. BAL fluid in PAP is classically milky in appearance and shows large amounts of PAS-positive lipoproteinaceous material1. Treatment depends on the severity of illness. Mild cases may be observed, while patients who are symptomatic or shown signs of progressive disease may be treated with whole lung lavage (WLL). Standard treatment is management of the underlying inciting trigger and treatment with recombinant GM-CSF subcutaneously if auto-antibodies are present. Inhaled administration, although not FDA approved, has also shown benefit, especially in refractory cases such as our patient2,3 .

| Table 1. PAP etiologies1 | |

| Autoimmune | Antibodies against GM-CSF |

| Hereditary | GM-CSF receptor defects |

| Congenital | Defects in surfactant-related gene variants |

| Secondary | High level dust exposures Hematologic malignancies After allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation |

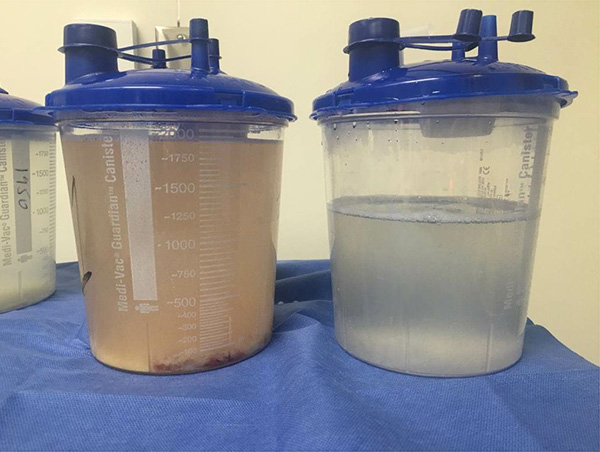

In this patient, the diagnosis of PAP was established based on clinical, radiologic and cytopathologic evidence. Clinically, he was found to have polymyositis and significant exposure history associated with PAP. BAL cytopathology (Figure 2A) showed Romanowsky stained slides with amorphous proteinaceous aggregates (arrowhead) and (Figure 2B) Papanicolaou stain showed many alveolar macrophages, some with engulfed amorphous material. The patient’s granulocyte monocyte colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) auto-antibody level was high and he was started on immunosuppressive therapy and subcutaneous recombinant GM-CSF (sargramostim). He underwent WLL with characteristic clearance of lipoproteinaceous sediment on each successive lavage (Figure 3), but required WLL every 3-6 months due to worsening of symptoms and infiltrates on imaging. Subcutaneous administration of recombinant GM-CSF was switched to nebulized administration and the patient has not required WLL since.

Figure 3. Total lung lavage. First fluid obtained (left), last fluid obtained (right). Note the lipoproteinaceous material sediment at the bottom.

Figure 4. Crazy paving pattern

References

-

Trapnell B, Whitsett J, Nakata K. Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 2527-39.

-

Reed J, Ikegami M, Cianciolo E, et. al. Aerosolized GM-CSF ameliorates pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in GM-CSF-deficient mice. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 1999; 276(4): L556-L563.

-

Yamamoto H, Yamaguchi E, Agata H, et. al. A combination therapy of whole lung lavage and GM‐CSF inhalation in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2008; 43: 828-30.