Clogged Pipe

Sarah Orfanos MD, Ibrahim El Husseini MD

Division of Pulmonary and Critical Medicine, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital.

Case

A 25-year-old female presented to the intensive care unit for altered mental status following a suicidal attempt and ingestion of an unknown substance. Patient was intubated for airway protection and treated with Fomepizole and hemodialysis and extubated within 24 hours. A few hours post-extubation, she developed inspiratory and expiratory stridor requiring reintubation. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest (Figure 1) and flexible bronchoscopy (Video 1) were performed for further evaluation.

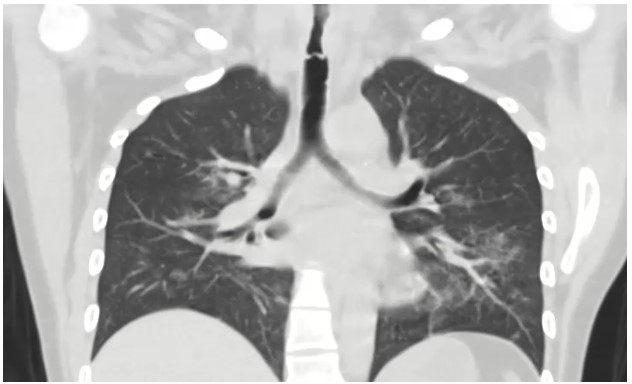

Figure 1: Post-extubation coronal computed tomography of the chest (parenchymal window)

Video 1: Diagnostic bronchoscopy with visualization of the trachea

Question

What is the etiology of the patient’s persistent stridor and respiratory distress?

- Tracheomalacia

- Post-intubation tracheal granuloma

- Tracheal caustic injury

- Tracheal tumor

- Tracheo-esophageal fistula

C. Tracheal caustic injury

Discussion

Tracheomalacia (answer A) would show dynamic collapse of the anterior wall of the trachea rather than extensive sloughing seen during bronchoscopy. Tracheal granulomas (answer B) are not commonly seen following brief intubation as with this patient and bronchoscopy would demonstrate granulation tissue rather than extensive injury and mucosal sloughing as seen here. A tracheal tumor (answer D) would manifest as a growth without extensive sloughing. A trachea-esophageal fistula (TEF, answer E), a connection between the trachea and esophagus, is generally diagnosed with bronchoscopy, though can be seen on CT or with barium swallow. TEF generally occurs in the setting of thoracic malignancy, with aspiration being the most common symptom.

CT chest in our case demonstrated circumferential tracheal narrowing on the coronal view (shown above), with a transverse band of tissue extending across the tracheal lumen. The tracheal lumen measured 5mm at its narrowest with audible stridor and respiratory distress, stressing the urgency of therapeutic bronchoscopy. Flexible bronchoscopy showed diffuse caustic tracheal injury, with extensive fibrin and necrotic tissue and a false membrane almost completely obstructing the trachea. We were able to remove the obstructing tissue using flexible forceps. Balloon dilatation or Argon Plasma Coagulation were not performed due to the high risk of tracheal perforation in the setting of caustic injury. The patient was successfully extubated and discharged. In the following months she underwent two flexible bronchoscopies with balloon dilatation due to persistent tracheal stenosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Bronchoscopy performed 3 months post initial injury showing improvement of the necrosis but development of scar tissue with tracheal stenosis

Caustic airway injury is less commonly reported than GI tract caustic injury, however, it can result in serious consequences, including tracheal perforation, necrosis or long-term complications such as tracheal stenosis. The pathophysiology of caustic injury varies depending on the proprieties of the ingested substance (acidic or alkaline). Alkaline agents cause tissue injury by liquefactive necrosis through saponification of fat. Acidic substances cause coagulation necrosis with denaturation of the superficial protein layer. These patients frequently require multiple bronchoscopies for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Acute therapeutic options include debridement (as performed in this case) and balloon dilatation, though dilation in this setting is associated with high risk of tracheal perforation(1). Alternative therapies once the inflammatory response settles include pulmonary patch repair (2), airway stenting, balloon dilation with or without heated ablative therapies, and slide tracheoplasty (3).

References

-

Hautefort C, Teissier N, Viala P, Van Den Abbeele T. Balloon dilation laryngoplasty for subglottic stenosis in children: eight years’ experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012 Mar;138(3):235–40.

-

Chiba S, Brichkov I. Pulmonary Patch Repair of Tracheobronchial Necrosis With Perforation Secondary to Caustic Ingestion. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014 Jun 1;97(6):2205–7.

-

Yong MS, Konstantinov IE. Understanding the impact of slide tracheoplasty in congenital tracheal stenosis. Transl Pediatr. 2019 Dec;8(5):462–4.