“Air in the Chest”

Scott Mayer, MD1, Daniel Kissau, MD1, Gregory Schlessinger, MD2

1Department of Medicine, HCA HealthONE, Denver, CO; 2Rocky Mountain Kidney Care, Denver, CO

Case

A 28-year-old female with no past medical history and no home medications presented to the emergency department with complaints of chest pain and shortness of breath of two days duration. She vomited three times and was unable to hold food down. She had previously been in good health. She denied fevers, chills, cough, wheezing, rhinorrhea, body aches, or other infectious symptoms. She endorsed recent inhaled cocaine use and continued nicotine use via vaporizer pen. Her vital signs were stable on room air, and her physical examination was benign.

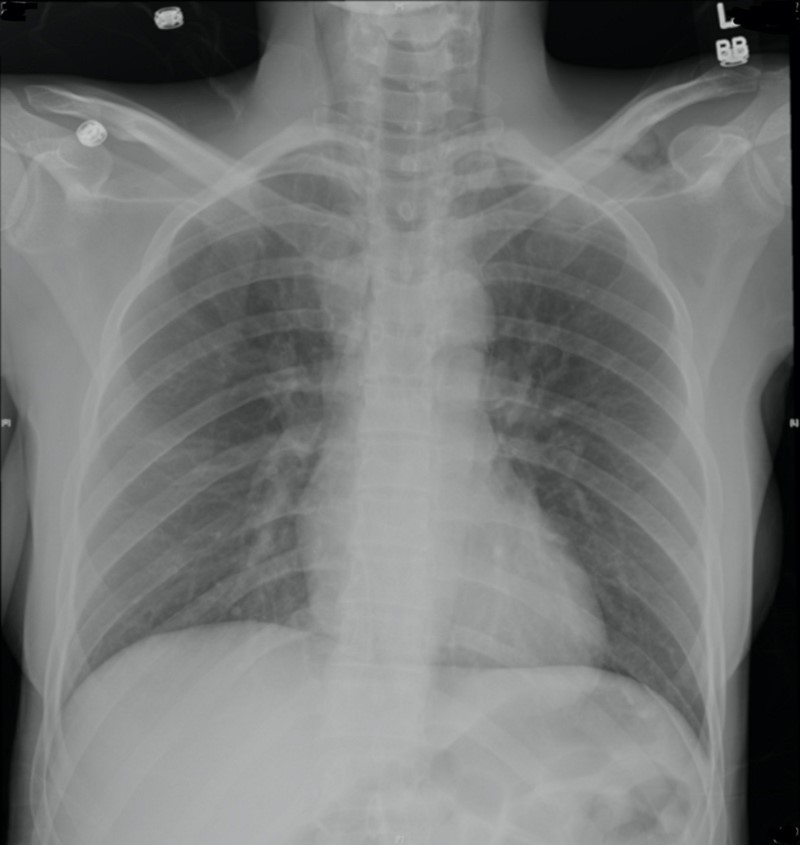

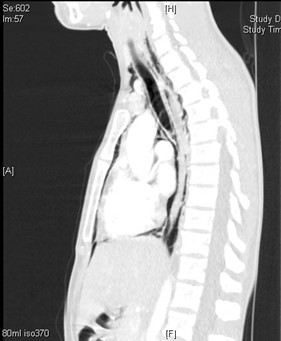

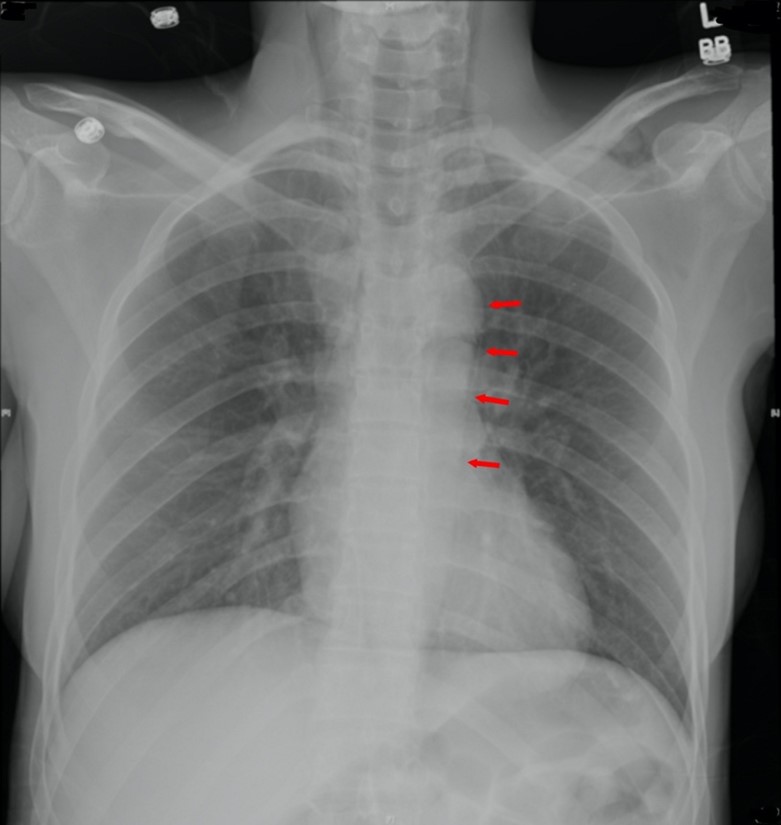

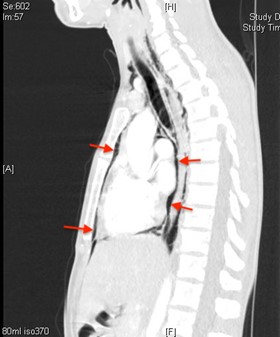

Her chest X-Ray and CT of the chest are shown below:

She subsequently had a CT Esophagram that demonstrated no extravasation of contrast.

Question

What is the most appropriate next step in work-up?

- Direct visualization of the airway

- Surgical washout of the mediastinum

- IV antibiotics

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

A. Direct visualization of the airway

Discussion

The most appropriate next step in the work-up is direct visualization of the airway with laryngoscopy or bronchoscopy in this patient who presented with pneumomediastinum in the setting of recreational drug and vaporizer use.

Air in the mediastinum is visualized on both the chest X-Ray and CT as below:

Our patient is at risk for tracheal perforation from the inhalation of caustic compounds, including oils from her vaporizer pen and the inhalation of cocaine. Therefore, evaluation of the patient’s airway via direct visualization is appropriate to rule out perforation of the trachea or bronchi.

CT Esophagram effectively rules out an esophageal perforation thereby negating the need for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (Answer D is incorrect). Furthermore, she presented with stable vital signs and no respiratory distress. Whereas if she had signs of sepsis or mediastinal fat stranding on imaging, acute mediastinitis would be a concern. In cases of acute mediastinitis, both IV antibiotics and a surgical washout of the mediastinum are urgently pursued (Answers B & C are incorrect).

Pneumomediastinum can be classified as spontaneous or secondary. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum is seen in otherwise healthy subjects without an obvious causative factor, although predisposing factors include tobacco and recreational drug use. Secondary pneumomediastinum can be associated with iatrogenic, traumatic, and non-traumatic causes.

In contrast to secondary pneumomediastinum, spontaneous pneumomediastinum is a relatively benign process with minimal morbidity or mortality. According to a metanalysis of 600 patients across 27 papers, there is an approximate 2.9% of associated morbidity with no reported mortality. However, secondary pneumomediastinum must be thoroughly ruled out before diagnosing primary pneumomediastinum. Patients may be observed to ensure stability prior to discharge and typically have resolution of subcutaneous emphysema within 7-10 days. While IV antibiotics are sometimes prescribed for these patients while under observation, they are not necessary given the absence of adverse outcomes.

Pneumomediastinum can be detected on chest X-ray with a sensitivity of ~70%-90%, sensitivity approaches 100% on CT scan. If pneumomediastinum is associated with a pneumothorax, the pneumothorax will likely justify further hospital stay and intervention.

Our patient presented with multiple risk factors for spontaneous pneumomediastinum including inhaled drug use, smoking, and vomiting (which causes an abrupt rise in intrathoracic pressure). The association between vaporizer use and pneumomediastinum has become more important to consider as vaporizer use has become more popular.

References

-

Alemu BN, Yeheyis ET, Tiruneh AG. Spontaneous primary pneumomediastinum: is it always benign? J Med Case Rep. 2021 Mar 25;15(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s13256-021-02701-z.

-

Caceres M, Ali SZ, Braud R, Weiman D, Garrett HE Jr. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a comparative study and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008 Sep;86(3):962-6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.067.

-

Alaska YA. Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum Secondary to Hookah Smoking. Am J Case Rep. 2019 May 6;20:651-654. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.915118.

-

Dajer-Fadel WL, Argüero-Sánchez R, Ibarra-Pérez C, Navarro-Reynoso FP. Systematic review of spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a survey of 22 years' data. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2014 Oct;22(8):997-1002. doi: 10.1177/0218492313504091.

-

Smith BA, Ferguson DB. Disposition of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Am J Emerg Med. 1991 May;9(3):256-9. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(91)90090-7.