A Perfect Cloudy Storm

Dr. Anne Coates

Barbara Bush Children's Hospital

Dr. Jonathan Mathes

Barbara Bush Children's Hospital

Case

A 22-month old female with trisomy 21 presented with acute hypoxic respiratory failure in the setting of four days of worsening cough, congestion, fever and increased work of breathing. Her past medical history was notable for left sided congenital chylothorax and congenital heart disease including partial anomalous pulmonary venous return repaired at 18 months via the Warden procedure.

Her physical examination revealed hypoxia, fever, tachypnea, subcostal retractions, scattered crackles and diminished right sided breath sounds. Furthermore, progressive upper extremity and facial edema developed during the admission.

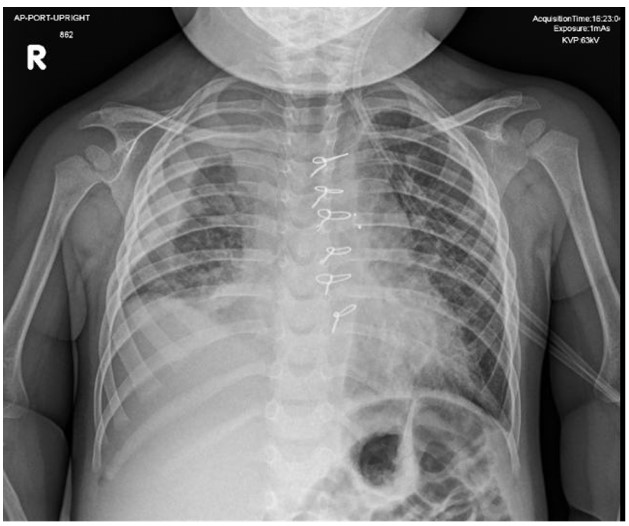

An initial 1 view CXR was obtained and revealed multifocal opacifications and a large right sided pleural effusion (Image 1).

She underwent diagnostic and therapeutic thoracentesis with chest tube placement. Pleural fluid studies revealed elevated triglycerides and leukocytes. A chest CT with angiography revealed high-grade stenosis in the proximal superior vena cava (SVC) at the site of the Warden repair.

Figure 1

Question

The fluid composition of the pleural effusion is:

- Serous

- Blood

- Chyle

- Pus

Answer C. Chyle

Discussion

Her physical examination, chest imaging and pleural fluid studies were consistent with chylous effusion secondary to SVC syndrome and anomalous lymphatic drainage.

Chyle is a noninflammatory, alkaline, and bacteriostatic fluid composed mainly of fat, cholesterol, electrolytes, proteins, glucose, and abundant lymphocytes. A chylothorax is defined as accumulation of chyle in the pleural space. 1,2 The thoracic duct transports between 1.5 and 2.5 L of chyle daily (maximum 4 L/day in a healthy adult). Flow varies depending on the diet, medications, intestinal function, and physical activity, and it can increase by two- to 10-fold for 2 to 3 hours after ingestion of fat, and by 20% after drinking water.2 Disruption to the thoracic duct may cause improper drainage and development of a chylothorax. 1,2 Complications include malnutrition, respiratory distress, thrombosis, fluid imbalance, and immunodeficiency (of note, our patient had low immunoglobulin levels during admission).

The pleural fluid studies revealed elevated triglycerides and leukocytes which is consistent with chyle and not serous, blood or pus.

There are several causes of chylothorax in infants and children which vary according to the age of the child or mechanism of injury to the thoracic duct. It may result from congenital abnormalities of the lymphatics, which do not always present in the neonatal period.2 Pulmonary lymphangiomas and lymphangiectasia are the 2 major lymphatic abnormalities associated with chylothorax.2 Our patient’s underlying risk factors created the perfect storm for the development of a chylous effusion:

- SVC narrowing from prior cardiac surgeries à elevated venous pressures in the region into which the thoracic duct drains à increase pressure within the lymphatic system3

- intrinsic lymphatic abnormality, associated with trisomy 21

- increased lymphatic flow from an acute infection

Following the initial chest tube placement, 300 mL of milky fluid was removed with improvement in her respiratory status. However, significant chest tube output persisted despite initiation of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) for a low fat diet. Ultimately, a SVC stent was placed after which there was resolution of the chest tube drainage. The chest tube was pulled and she was discharged home on a low fat diet.

Our patient was treated by Pediatric Hospital Medicine, PICU, Cardiology, Gastroenterology, Pulmonology, Immunology, Palliative Care, OT, PT, SLP, Nutrition services and underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary team approach to these complex diagnoses. At pulmonary follow up three weeks after her hospitalization, she was doing well with no change in symptoms or physical examination after transitioning to a regular diet.

References

-

Tutor, J. D. (2014). "Chylothorax in Infants and Children." Pediatrics 133(4): 722-73

-

Solo-Martinez, M., et al. (2009). "Chylothorax: diagnosis and management in Children." Paediatr Respir Rev10(4):199-207

-

Nossair, F., et al. (2018). "Pediatric superior vena cava syndrome: An evidence-based systematic review of the literature." Pediatric Blood & Cancer 65(9): e27225