A 37-year-old Man with Dyspnea and Pulmonary Nodules

Karen Flores Rosario MD1, Yasmeen M. Butt MD2, Chad Newton MD3

1 Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas - Southwestern

2 Department of Pathology, Division of Thoracic Pathology, University of Texas - Southwestern

3 Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Pulmonary Medicine, University of Texas - Southwestern

Case

A previously healthy 37-year-old man presented to the emergency department with one month of worsening dyspnea on exertion and intermittent pleuritic chest pain. He had not experienced fevers, chills, cough, night sweats, anorexia, or hemoptysis. He took no medications. He smoked 1-2 cigarettes/day for the last 20 years. He was a construction worker and cut natural stone for swimming pools. He lived on a ranch with exposures to dogs, cats, birds, and horses. On physical exam, he had normal vital signs, heart rhythm and rate were regular, and lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. Joint and skin exam were unremarkable.

Infectious workup was unremarkable. Spirometry revealed low-normal lung volumes and diffusion capacity and no response to bronchodilators. Autoimmune workup revealed non-specific positive findings consisting of the following: Antinuclear Antibody 1:2560, speckled pattern, Rheumatoid Factor 27, Anti-Ro/SSA>8, Anti-La/SSB >8, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 84.

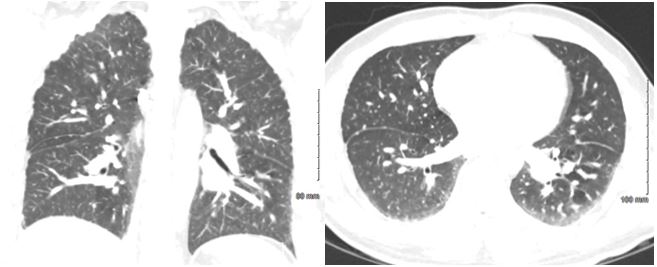

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the chest is shown below.

Images A & B

Initial bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of the right middle lobe revealed a hazy colorless fluid with 1315 nucleated cells, 125 red blood cells, and macrophages with hemosiderin or ingested material. Given inconclusive findings of BAL, a video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) wedge biopsy of the right upper and lower lung lobes was performed.

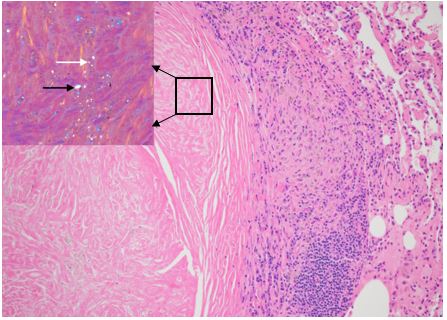

Image C

Question

What would you do next?

- Advise smoking cessation and treat with oral steroids.

- Advise smoking cessation and avoidance of silica exposure.

- Initiate bronchodilators.

- Perform whole lung alveolar lavage.

B: Advise smoking cessation and avoidance of silica exposure.

Image A - Coronal and axial chest CT angiography images demonstrate no pulmonary embolism but presence of innumerable perilymphatic and centrilobular pulmonary nodules predominantly in a mid and upper lung zone distribution.

Image B - Hematoxylin & Eosin stain from surgical lung biopsy illustrating a centrally fibrotic and acellular pulmonary nodule composed of whorled collagen, bordered by lymphocytes and dust-laden macrophages. Under polarized light, weakly birefringent polarizable particles (white arrow) and strongly birefringent particles (black arrow) are visualized. Magnification 20X

Discussion

The correct diagnosis is suggested by the combination of clinical history of prolonged silica exposure, CT findings, and VATS findings of weakly birefringent silica crystals. The timing of exposure to silica is particularly important as the cumulative dose of silica is the most significant factor leading to silicosis.1 The majority of times a silicosis diagnosis can be made by the history of silica exposure and imaging features but other competing diagnoses must also be excluded (e.g. miliary tuberculosis, endemic fungal infection, metastatic carcinomas, sarcoidosis, and other fibrotic interstitial lung diseases). Chest CT is more sensitive than chest radiograph in detecting conventional features of silicosis such as bilateral air-space disease with consolidation in the posterior portions of the lungs and centrilobular nodules.1

Given the need to rule out other processes based on the broad differential diagnosis generated from this patient’s history and imaging, a bronchoscopy was conducted. In this case, the bronchoalveolar lavage culture was negative and the transbronchial biopsy was non-diagnostic. Therefore, a surgical lung biopsy was performed which revealed classic, sharply circumscribed nodules with weakly birefringent silica particles and strongly biregringent silicate particles visualized under polarized light consistent with a diagnosis of silicosis. Given the pattern of small innumerable nodules on chest imaging and normal lung function, the patient was diagnosed with simple silicosis. The biopsy samples were negative for mycobacterium, fungi, and malignancy. This is important to note as silicosis is associated with an increased risk of lung cancer and infections such as tuberculosis. 1

Silicosis has been considered a risk factor for the development of rheumatologic disease as silica particles are identified as danger signals by the inflammasome and lead to activation of T and B lymphocytes resulting in increases in antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and immunoglobulins. 2 Our patient’s autoimmune workup during his initial presentation was concerning for existing autoimmunity and in a follow-up encounter he presented with symptoms of dry mouth and dry eyes in addition to positive Anti-Ro/SSA, Anti-La/SSB and was diagnosed with Sjogren’s syndrome.

Currently, there is no treatment for silicosis and patients are advised to avoid silica exposure and to wear respiratory protective equipment to minimize the degree of exposure. There is no evidence that corticosteroid therapy alters the course of the disease without removal of the offending exposure. Bronchodilators may be considered for symptomatic patients with airflow obstruction on spirometry testing. There is no conclusive evidence that whole lung alveolar lavage is beneficial in these patients.3

There are roughly 2.2 million workers exposed to silica in the US. There are different types of silicosis: chronic silicosis which develops after greater than 10 years of exposure and is associated with progressive massive fibrosis, accelerated silicosis which develops after 5 to 10 years of exposure, and acute silicosis which develops within weeks to 5 years of exposure and is associated with silicoproteinosis. 1 Given these different degrees of exposure leading to silicosis, it has been key to reduce occupational exposure limits. In 2014, the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) lowered the occupational exposure limit from 0.1 mg/m3 (0.25 mg/m3 for the construction industry) to 0.05 mg/m3 with the hope of limiting silicosis and silicosis-associated illness such as lung cancer.4 Among smokers exposed to silica, the hazard ratio of lung cancer death is 5.07 (3.41–7.52) versus 1.60 (1.01–2.55) among non-smokers exposed to the same dose of silica (>1.12 mg/m3).5 Hence, this patient should be advised to avoid further silica exposure and quit smoking to help reduce his lung cancer risk.

References

-

Leung CC, Yu IT, Chen W. Silicosis. Lancet 2012; 379(9830): 2008-18.

-

Lee S, Hayashi H, Mastuzaki H, et. al. Silicosis and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 17(2): 78-84.

-

Greenberg MI, Waksman J, Curtis J. Silicosis: a review. Dis Mon 2007; 53(8): 394-416.

-

Deslauriers JR, Redlich CA. Silica exposure, silicosis, and the new Occupational Safety and Health Administration Silica Standard. What pulmonologists need to know. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15(12): 1391-2.

-

Liu Y, Steenland K, Rong Y, et al. Exposure-response analysis and risk assessment for lung cancer in relationship to silica exposure: a 44-year cohort study of 34,018 workers. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 178(9): 1424-33.