Pooja Belligund, M.D.

Fellow

SUNY Downstate Medical Center

Ghassan Jamaleddine, M.D.

Director

Divison of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine

Kings County Hospital Center

History

A 52 year old man presented to the ED with acute onset nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain that occurred while consuming alcohol. He reported sudden onset severe abdominal pain radiating to his back. In addition, he reported symptoms of cough with yellow sputum associated with fever and chills following the onset of vomiting.

Past medical history was significant for hypertension, hepatitis C, rheumatoid arthritis, schizophrenia and alcohol abuse.

Physical Exam

Unremarkable except for temperature of 100.8° F and mild epigastric tenderness. There was no involuntary rebound or guarding.

Chest X-Ray chest was read as normal

Course

He was admitted to the medical floor with a diagnosis of upper GI bleed, and started on IV proton pump inhibitor, kept NPO and scheduled for an upper endoscopy. The patient continued to have 1-2 episodes of vomiting after admission.

The next day the patient was febrile with a T max of 102ºF, he was tachypneic with an oxygen saturation of 77% on room air. He was in moderate respiratory distress with a respiratory rate of 30 per minute.

The exam was now notable for bilateral rales and bronchial breath sounds at the left base. The trachea was intubated and positive pressure ventilation was begun. The patient was transferred to the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU). Blood cultures were drawn, and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics (piperacillin/tazobactam, vancomycin and azithromycin) was initiated for presumed aspiration pneumonia.

Further work up was notable for the following:

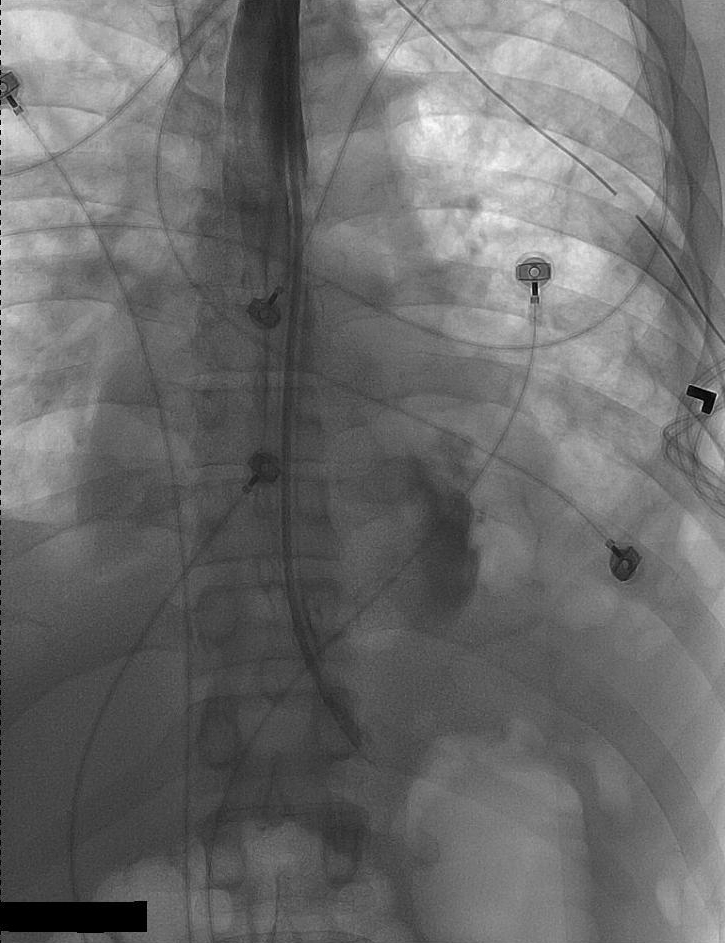

Peripheral WBC count = 14,000/cubic millimeter, and the chest x-ray (fig. 1) showing bilateral air space disease, left pleural effusion, pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema. Review of the admission CXR revealed air in the soft tissue of the neck on the right side

Figure 1: Chest X-Ray hospital day 2

Esophageal perforation was suspected and a chest tube was placed that yielded 700 ml of cloudy pink fluid

The results of the pleural fluid analysis are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pleural fluid test |

Results |

|

pH |

6.4913 |

|

AFB |

Negative |

|

Culture |

Strep.Viridans |

|

Protein |

3.9 g/dL |

|

Albumin |

2.0 g/dL |

|

Amylase |

20140 units/L |

|

Glucose |

30 mg/dL |

|

WBC |

14,600/cubic millimeter, 89% neutrophils |

Pleural fluid studies were consistent with esophageal rupture. GI service and CT surgery were consulted; the patient underwent an esophagogram that localized the site of the perforation.

Figure 2: Esophagogram

The esophagogram revealed extravasation of dye into the mediastinum and the presence of a perforation in the lower left portion of the esophagus.

The patient underwent an emergent exploratory thoracotomy that revealed a large distal esophageal tear with collection of purulent fluid in the left pleural space.

This collection was evacuated and the tear was repaired with an intercostal flap. A gastrostomy and jejunostomy was performed.

He had a prolonged stay in the SICU complicated by dehiscence of his abdominal wound and leakage from his esophageal repair. He also required a tracheostomy for respiratory failure.

He was transferred out of the SICU after six weeks to a regular surgical floor and was discharged to inpatient psychiatric care.

Question 1

The classic triad of vomiting lower chest pain and subcutaneous emphysema is seen in which of the following clinical entities?

a) Mallory-Weiss syndrome

b) Boerhaave’s syndrome

c) Aortic dissection

d) Pancreatitis

e) Gastro esophageal reflux

Answer to Question 1

(b) Boerhaave’s syndrome.

Boerhaave’s syndrome or spontaneous post emetic esophageal rupture was first described in a Navy admiral by Herman Boerhaave. Boerhaave’s syndrome is thought to be caused by the rapid increase in intraluminal esophageal pressure through the patient’s lower esophageal sphincter during forceful vomiting. The cricopharyngeal muscle fails to relax resulting in this sudden increase in pressure (1).This leads to transmural rupture in the esophageal wall. A large, rapid and transient transmural pressure gradient also exists in Mallory-Weiss tear. The resulting mucosal tear may result in profuse bleeding due to the rich vascular plexus that is torn with the mucosa. However, in a Mallory-Weiss tear, the remainder of the esophageal wall remains intact. Rarely, a Mallory-Weiss tear can progress to esophageal rupture (2).

Question 2

What is the main abnormality on this chest radiograph (Figure 3)?

a) Widened mediastinum

b) Bilateral airspace disease and pleural effusion

c) Left sided pleural effusion, subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum

d) Left lower lobe atelectasis

e) Pulmonary edema

Answer to Question 2

(c) Left sided pleural effusion, subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum.

Chest x-ray is abnormal in 90% of cases of esophageal perforation but can be normal if taken early (3). Pneumomediastinum may be seen as demonstrated above by the radiolucent streaks of free air surrounding the trachea.

Cervical perforation may result in right sided pleural effusion and pneumomediastinum while lower and middle esophageal disruptions tend to be associated with left sided pleural effusion (4).The gold standard for diagnosis is to perform a contrast enhanced esophagogram, initially with water-based contrast such as gastrograffin. If this study is negative and the index of suspicion is still high, diluted barium contrast should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and localize the perforation.

Question 3

The following are the results of the patient’s pleural fluid analysis.

|

Pleural fluid test |

Results |

|

pH |

6.4913 |

|

AFB |

Negative |

|

Culture |

Strep.Viridans |

|

Protein |

3.9 g/dL |

|

Albumin |

2.0 g/dL |

|

Amylase |

20140 units/L |

|

Glucose |

30 mg/dL |

|

WBC |

14,600/cubic millimeter, 89% neutrophils |

Which of the following are most suggestive of an esophageal rupture?

a) Elevated white blood cells.

b) Decreased glucose.

c) Elevated amylase and low pH.

d) None of these values are suggestive of esophageal rupture.

e) Positive culture suggests this is not an esophageal rupture.

Answer to Question 3

(c) Elevated amylase and low pH.

If pleural fluid is collected by thoracentesis, a pH of less than 6, presence of food particles or presence of elevated salivary amylase levels confirms the diagnosis (4). The low pH is thought to result from gastric acid and pleural inflammation.

Question 4

Which of the following factors have been shown to have a negative impact on the prognosis of esophageal rupture?

a) Delay in primary repair of the perforation and underlying physical status of the patient.

b) Presence of hematemesis

c) All patients have a dismal prognosis.

d) Iatrogenic injury leading to esophageal rupture

e) Presence of chest pain and vomiting

Answer to Question 4

(a) Delay in primary repair of the perforation and underlying physical status of the patient.

The critical determinants of therapy for esophageal perforation are the cause, the location, and the severity of the perforation, as well as the interval between perforation and treatment. In addition to the age and general health of the patient, the damage to surrounding tissues and the presence of concomitant esophageal pathology or injury must be considered before initiating therapy.(1,4)

Question 5

Which of the following is the leading cause of esophageal perforation?

a) Post emetic spontaneous esophageal perforation.

b) Trauma

c) Foreign body ingestion

d) Iatrogenesis

e) Tumor

Answer to Question 5

d) Iatrogenesis

Brinster et al (6) reviewed the literature between 1990 and 2003 and found 559 cases of esophageal perforation and the etiology was as follows:

Iatrogenic Injury/instrumentation-59%

Spontaneous perforation-15%

Foreign body ingestion-12%

Trauma-9%

Operative injury-2%

Tumor-1%

Others-2%

Esophageal perforation should be considered in patients complaining of chest pain after instrumentation.

References:

- Wu JT, Mattox KL,Wall MJ;Esophageal perforations:New perspectives and treatment paradigms. J Trauma 2007; 63:1173.

- Curci J, Horman M,Boerhaave's Syndrome:The Importance of Early Diagnosis and Treatment. Ann.Surg 1976, 183:401.

- Han SY, McElvein RB, Aldrete JS, Tishler JM: Perforation of the esophagus: correlation of site and cause with plain film findings. Am J Roentgenol 1985;145:537.

- Vial CM, Whyte RI. Boerhaave’s syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Surg Clin N Am 2005; 85:515.

- Attar S, Hankins JR, Suter CM, Coughlin TR, Sequeira A, McLaughlin JS. Esophageal perforation: a therapeutic challenge. Ann Thorac Surg 1990; 50:45.

- Brinster et al, Management of esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg 2004; 77:1475.