Answer: A. Aspergilloma

Aspergillus is a ubiquitous soil-dwelling organism. It is usually acquired by the inhalation of airborne spores. It grows best at 37°C, and the small spores, which measure between 2 and 3 µm, are easily inhaled and deposited deep in the lungs. This can cause a variety of clinical syndromes and, although these are distinct pulmonary entities, on rare occasions one condition may change to another.

Inhalation of Aspergillus spores by a normal host should not have any clinical consequences. However, inhalation of the spores by a patient with baseline lung disease or by an immunocompromised patient can cause a number of diseases.

An aspergilloma consists of masses of fungal mycelia, inflammatory cells, fibrin, mucus and tissue debris, usually developing in a preformed lung cavity. The most common predisposing factor is the presence of a pre-existing lung cavity. In the majority of cases, the lesion remains stable. Approximately 10% of aspergillomas decrease in size or resolve spontaneously without treatment. Rarely, the aspergilloma increases in size (1). Most are asymptomatic, sometimes for years, and are only picked up incidentally. It can present as hemoptysis, which is occasionally severe. It may present as a chronic cough or dyspnea.

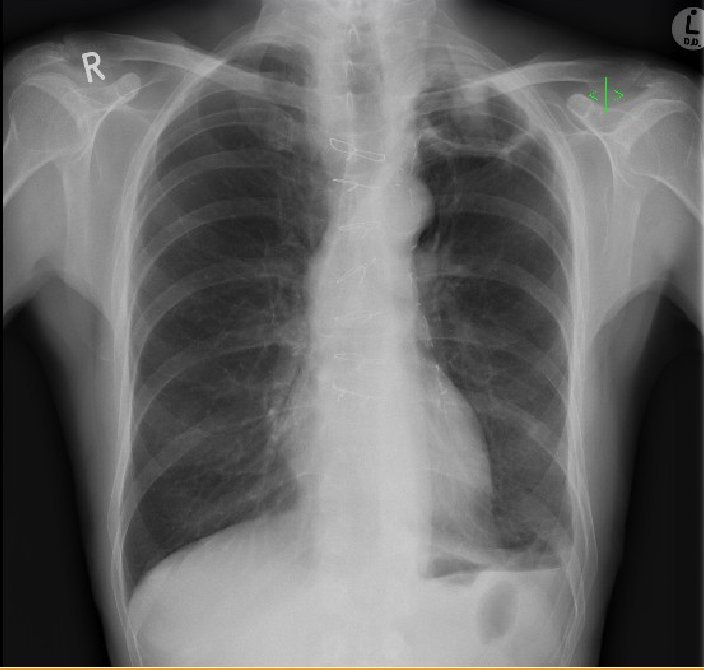

Radiologically, aspergilloma is evident as an upper-lobe, mobile, intracavitary mass with an air crescent in the periphery. CT may be necessary to visualize the aspergilloma. A change in the position of the aspergilloma with a change of position of the patient is an interesting but variable sign. Sputum culture may reveal the presence of Aspergillus but is negative in 50% of the cases (1). Serum IgG antibodies to Aspergillus are positive in almost all cases; however, they may be falsely negative in the rare cases of aspergilloma due to species other than A. fumigatus or in patients receiving corticosteroid therapy.

For asymptomatic patients, there is no need for any treatment. There is no consistent evidence that aspergilloma responds to antifungal agents such amphotericin B or voraconazole. Intracavitary or endobronchial antifungal administration can be used, but this is generally reserved for patients with severe hemoptysis. Surgical treatment of aspergilloma is associated with relatively high mortality rate that ranges between 7 and 23% (1). There is also considerable postoperative morbidity such as bleeding, residual pleural disease, bronchopulmonary fistula, empyema and respiratory failure.

Further history:

The patient subsequently became short of breath and developed a cough productive of green sputum. He was afebrile and had crackles in the left-upper lobe on respiratory exam.

Labs

White cell count 12.5 x109/l (4-11 x109/l)

Neutrophils 9.3 x109/l (2.0-7.5 x109/l)

Eosinophils 0.2 x109/l (0.0-0.4 x109/l)

Arterial Blood Gas on Room Air

pO2 10.61 kPa (79.8 mm Hg)

pCO2 3.86 kPa (29 mm Hg)

pH 7.49

HCO3 23.7 mmol/l

Pulmonary Function Tests

FEV1 56% predicted

FVC 80% predicted

FEV1/FVC 53%

TLC 84% predicted

RV 98% predicted

DLco 33% predicted

Figure 4. Air-fluid level in apical cavity with adjacent upper-lobe consolidation.

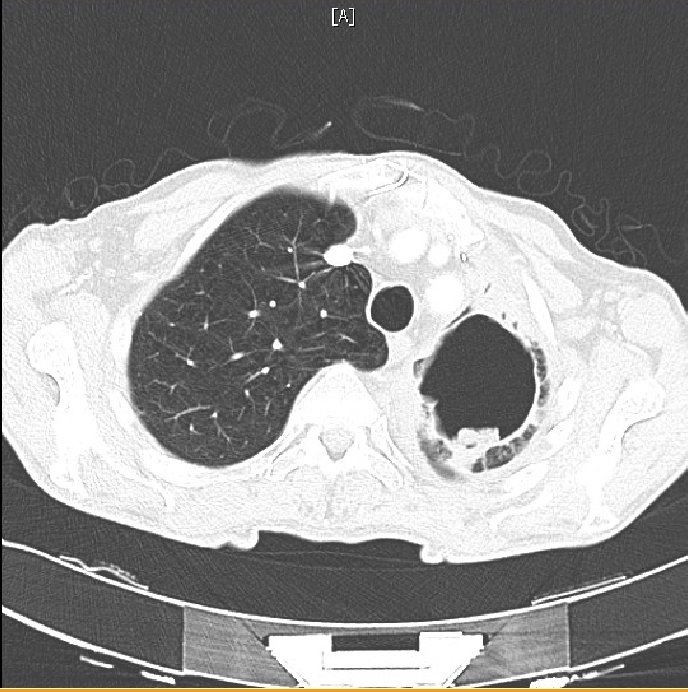

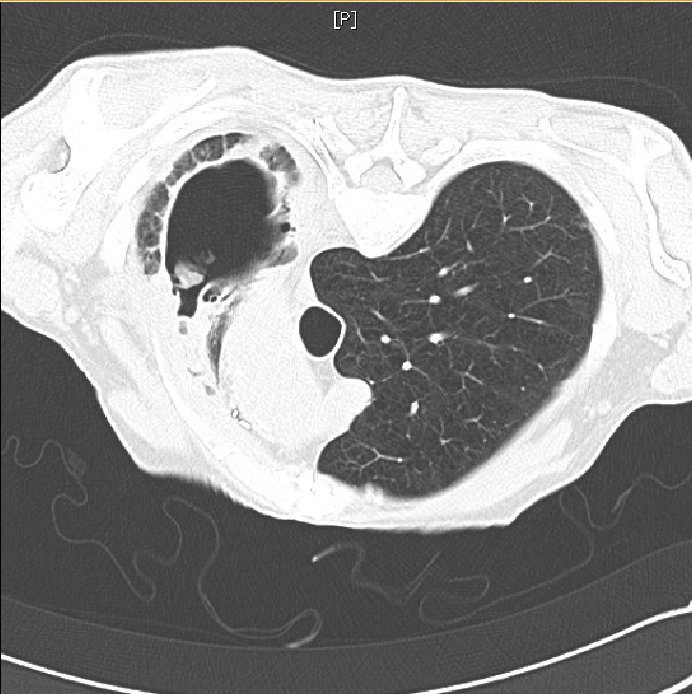

Figure 5. CT Angiography. No pulmonary embolus was identified, a consolidation surrounding the cavity was seen and new “tree-in-bud” opacification was present in the right-lower lobe.

Answer: E. both a and c above

The consolidation surrounding the cavity on CT and the new tree-in-bud opacification are suggestive of pulmonary infection, be it bacterial or fungal. This upper-lobe consolidation is also apparent on the plain chest radiograph, as is an air-fluid level. The above findings would be consistent with bacterial pneumonia, and the presence of an aspergilloma-containing cavity increases the susceptibility to bacterial infection. The clinical picture would also be consistent with a bacterial superinfection – cough productive of green sputum, upper-lobe crackles on auscultation and raised white cell count with associated neutrophilia. Diagnosis would be based on a positive bacterial culture on sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage specimens, and clinical and radiological improvement with appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Chronic necrotising aspergillosis (CNA) is an indolent, destructive process of the lung due to invasion by Aspergillus. It is characterized by local invasion of the lung tissue. A pre-existing cavity is not needed, although a cavity with a fungal ball may develop as a secondary phenomenon due to destruction by the fungus. It is also different from invasive aspergillosis in that it is a chronic process that progresses slowly over months to years, and there is no vascular invasion or dissemination to other organs.

It most commonly affects middle-aged and elderly patients and those with underlying lung diseases – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inactive tuberculosis, previous lung resection, radiation therapy, cystic fibrosis, lung infarction. It can also affect those with mild immunosuppression – patients with diabetes mellitus, connective tissue diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, poor nutrition and those on low-dose steroids.

Clinical features include fever, cough, sputum production and weight loss of 1 to 6 months duration. Chest radiograph usually shows an infiltrative process in the upper lobes or the superior segments of the lower lobes. A fungal ball may be seen in nearly half of the case (2). Adjacent pleural thickening is a characteristic finding and may be an early indication of a locally invasive process (3).

Clinical diagnosis of CNA can be made using the following criteria (1):

- Clinical and radiologic features consistent with the diagnosis

- Isolation of Aspergillus species by culture from sputum, bronchoscopic or percutaneous samples

- Exclusion of other conditions with similar presentations, such as active tuberculosis, atypical mycobacterial infection, chronic cavitary histoplasmosis or coccidioidomycosis

Treatment is with antifungals such as intravenous amphotericin B. However, voriconazole has emerged as an effective alternative (1). Surgical resection is generally reserved for healthy young patients with focal disease and good pulmonary reserve.

Answer: C. Voriconazole

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is a severe and life-threatening disease affecting patients with prolonged and severe neutropenia. It most commonly occurs in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell or solid organ transplantation. Sinopulmonary disease is the most common presentation. Early diagnosis is difficult. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cultures have a 50% sensitivity in focal pulmonary lesions (5). Definitive diagnosis often requires an invasive procedure, but isolation of Aspergillus from sputum or BAL is highly predictive of invasive disease in neutropenic patients (5).

One or more nodules is the most common finding on chest CT in early IPA in neutropenic patients and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, and may be inapparent on chest radiograph.

A combination of the following will give you a diagnosis of “probable invasive aspergillosis,” and therefore there is no need for an invasive procedure (5).

- Predisposing host factors

- Compatible clinical and radiological findings

- Two consecutive positive serum galactomannan assays

Treatment is primarily medical, with appropriate antifungal agents, although surgery can be used to debride necrotic tissue and to remove infected tissue. It is also indicated for pericardial infection, empyema, invasion of the chest wall and persistent hemoptysis. Surgical excision of a cavity has been performed in patients with a single pulmonary lesion and recurrent hemoptysis or bacterial superinfection. There is also a role for reversal of the immunosuppression with colony stimulating factor (CSF), which can reduce the incidence or neutropenic fever by up to 50% (5).

However, the mainstay of treatment is with voriconazole (4). The recommended dose is 6 mg/kg bid iv on day 1, then 4 mg/kg bid iv, switching to 200 mg bid po when stable.

A combination of voriconazole and an echinocandin can be used for salvage therapy. It is suggested to continue antifungal therapy until all signs and symptoms as well as radiographic evidence of the infection have resolved for at least 2 weeks (4).